Before one sails towards Antarctica, you must get as far south as possible. Some seven thousand miles south of Salt Lake City is the city of Ushuaia. “Fin del mundo, principio de todo,” the end of the world, beginning of everything, is our launching off port for our expedition to the seventh continent. A quaint city of over 80,000 inhabitants, the surrounding landscapes and the weather enveloping our surroundings remind us of the challenges that lie ahead. Winds gusting beyond 30 knots proved to be too much for most of the general aviation action happening just south of the port, where one lone PA-28 was braving the winds until they finally threw in the towel. These winds proved to be even too much for the MS Fritjof Nansen, which caused a delay the departure of our home for the next nine days while the winds and sea state were forecasted to be more favorable later in the evening.

Known for being home to some of the most treacherous conditions at sea, the Drake Passage is agenda item one for the first two days of our voyage. Some six hundred miles of the Drake welcomed us to the Southern Ocean with waves in excess of twelve feet, and swells approaching similar heights. The first few days on the ship were quite pleasant, as many of our fellow adventurers likely dealt with the physiological challenges of traveling to the southernmost city in the world, many from Eastern Asia and Western Europe, likely complicated with many learning how their sea legs work. Crossing the Drake availed some of us opportunities to get caught up on sleep, while others wrestled pitching decks and sea spray to start observing some of the pelagic birds common to these waters. At least seven new species on the life list, the anticipation for what lies ahead kept me awake, and likely warm as well.

Eventually, the first icebergs were spotted as we approached the Antarctic Peninsula. Our first stop, a mystery to most on the ship, was the Yalour Islands. How did I know? Easy. Ships like the Nansen have automatic position reporting systems, like ADS-B, that permit the destination be added to their transmissions. Surely, one could have been at the Expedition Team’s briefing for the following day to hear what was up, but I knew before them thanks to a few website that aggregate these AIS reports and allow you to track thousands of ships at sea. But before we got there, a few of us early risers saw the first icebergs. Stark white, tints of turquoise blue, these floating frozen bodies of water were sometimes refuges for penguins, seals, and wandering eyes of those braving the bitter conditions on Decks 6, 7, and 10. The various shapes and sizes alerted us that we’re slowly approaching the white continent. Two days of bobbing and weaving in the Drake now culminating in this precious moment, that appeared hidden behind a wall of snow that obscured forward visibilities and made one wonder if they were ever going to see the continent.

As if scheduled, the snow subsided. Visibilities gradually increased, and the sun, having been hidden most of the morning, found a small break in the clouds to help dry off the tears shed as for the first time, Antarctica was in sight. Sailing through the Grandidier Channel, the islands of the Wilhelm Archipelago became the foreground to the various outcroppings of the western coast of Graham Land. A moment that had been in the making for many years, the anticipation of seeing more and more of this barren, desolate, breathtaking wilderness negated the multitude of layers one thought would be required to sustain life. Instead, the errant penguin chatter, the humpback’s blow, the waves crashing in and around the icebergs invigorated the adventurers in us all, to hurry down to the girl’s cabin, and to share with them the great news.

Taking the extra 80 liters of gear we packed for their first out-of-the-package experience, the Evans Consortium donned multiple layers and assembled at the Expedition Launch for our first time off the ship in three days. Riding zodiacs around the Yalour Islands, we would be given our first chance to see, up close, what Antarctica looked like. Wool under layers covered in various sweaters, jackets, and waterproof pants and weatherproof layers provided the protection we thought we would need from the harsh conditions of Antarctica’s summer. In reality, the 32º Fahrenheit temperatures and light winds proved to be quite mild for a family whose last breaths at home were after a night of 1-2 inches of snowfall in the valley floor. While the mad rush of adventurers heading through the Expedition Launch caused our party to get separated for a bit, we slowly realized that amongst the seven in the Consortium, our future disembarkations and meals would be amongst an even larger contingent of family, as one of my coworkers’ families, an additional Delta Pilot Wife, and a few more pilots we met on the ship would be honorary members of the Consortium. Thankfully, our favorite lunch spot on the ship had a table that could accommodate us all.

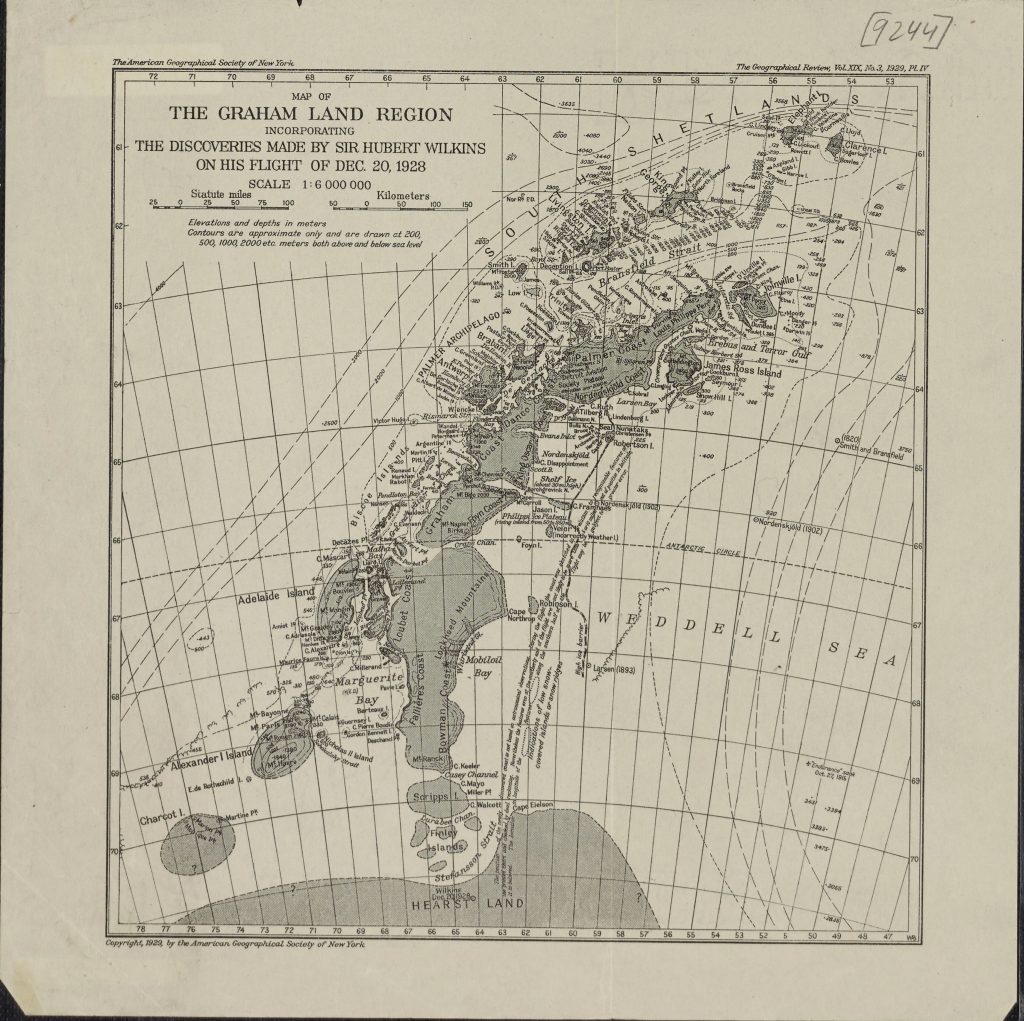

Before heading down south, I spent a considerable amount of time trying to gather some maps and charts of Antarctica. One of my favorites, this first one is quite unique. Sir Hubert Wilkins was an Australian combat photographer, who, in World War I, was the first (and only) one of his kind to receive a combat metal for “acts of exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy on land.” His observational skills were then put to use as part of what historians refer to the last voyage of the golden era of Antarctic exploration, serving as the expedition’s biologist (specifically, ornithologist). Later, these skills were then further put to use in other Arctic and Antarctic explorations. Wilkins and his co-pilot Carl Ben Eielson were the first pilots to fly over Antarctica, departing from Deception Island in December 1928. This map was drawn from the observations they made flying over 600 miles. One of those features noted was the “Evans Inlet,” now called the Evans Glacier, that he named after E.S. Evans, who was a pioneer in aviation in the Detroit area. Interestingly enough, our first landing in Antarctica was just opposite of the Evans glacier, but I digress.

Cruising around the Yalour Islands, we got our first experience with one of the most beautiful, foul-smelling things I’ve ever seen. One of four species of penguins we would see on our expedition, the Adélie penguins have made these islands their home. Having come at what appeared to be the perfect time (just like we experienced in the Galapagos), we found ourselves witnessing the circle of life in full effect. Eggs, freshly-hatched fledglings, and even a few late comers to the mating party were seen enjoying the snow-free outcroppings of rock across these islands. The Adélie penguins are distinguishable from the others due to their all-black heads and white halos around their eyes. Much like other penguins, their young are grey and furry, awaiting a time in their upcoming lives to go through what ornithologists call a catastrophic molt, where their non-water-resistant feathers are replaced by the white and black feathers of their parents.

After a quick lunch back on the Nansen, the Evans Consortium completed that which was the reason behind this great voyage. Landing on the shores of Petermann Island by zodiac in many layers (maybe one or two less this time), after a short hike, we stood together as a family and marked the completion of visiting all seven continents as a family of seven in under seven years. Certainly the furthest we’ve been away from home, and the most arduous journey to cross one off this list, the excitement of fulfilling our mission once again kept us warm, and added to the excitement that as this was only day one of five on the continent, we had many more adventures ahead of us. A ship filled with over 400 other adventurers meant that some of the limited opportunities to snowshoe, kayak, and camp in Antarctica would be at the luck of the draw. Having returned back to the Nansen after leaving our footprints on Petermann Island, we learned that Luke, Matt, and I were drawn to snowshoe on Hovgaard Island on the following morning, and to camp in bivvy bags on the famous Damoy Point, and that our entire family would get to kayak at some point in the future as well.

On the schedule, the following day was going to be the most action packed. Starting the morning off a little earlier than before, Luke, Matt, and I landed on Hovgaard Island to enjoy a few miles of snowshoeing. While we were making our way on land, the rest of the Consortium took to the zodiacs to tour around the area. Once all were back onboard, the Captain had made plans to sail the Lemaire Channel, one of the most breathtaking vistas that at first glance didn’t appear to have enough room for the Nansen to sail through. While we were finishing our lunch as a group of fourteen, the rock outcroppings outside the window started to appear closer than before. Immediately, we ran to the bow to hear the ship’s historian Magnus tell us the tale of the Begica, the first ship to sail through this channel, who’s Norwegian accent reverberated through the narrow passageway.

Days talking about it at lunch and dinner, the Polar Plunge was part of the afternoon’s itinerary. Having heard Magnus make his last plea to the “sheer stupidity” of people who’d dare to jump into freezing waters, Kenzi, Luke, Matt, Stefani, and I made our way to the Expedition Launch in less than usual layers, sporting nothing beyond a swimsuit and our bath robes. Having psyched ourselves out with rumored tales of one or two people who perished plunging into these frigid waters, the anticipation (and the donning of a freshly-plunged life jacket) were honestly the hardest parts of the jump. The waters near Cape Renard, and the scenery of the Hidden Bay, were the perfect backdrop to a once-in-a-lifetime experience, willingly jumping into waters colder than freezing, for a few mere moments of adrenaline spiking through your veins while you realize that a few months of cold showers in preparation for this moment were nowhere near what you’d experience. I’ll never forget having felt so alive as I found myself deep within the coldest, saltiest water ever.

Having won the camping lottery, Luke, Matt, and I left the safe confines of the Nansen having spent a few hours warming back up in the hot tub and sauna and took to the zodiacs to land on Wiencke Island, our home for the night. Having attended the requisite briefings, we were well versed on what to expect, minus the size of the backpacks that would be carrying our bivy bags, sleeping bags, sleeping pads, and pillows. Nonetheless, a short hike from the shore to a few hundred meters uphill from the Damoy Hut, we found some almost level terrain where we would be digging our sleeping pits for the night, a foot deep below the surface and the size of a normal sleeping bag. The pits allowed us some relief from the evening breezes, but certainly did not help with the rain and snowfall that predominated the evening. Only the clocks could help us understand it was evening, as the skies remained bright all evening. Case in point…the picture above was taken just after 11:00 pm, when we finally retired from a brief hike up to the top of the island.

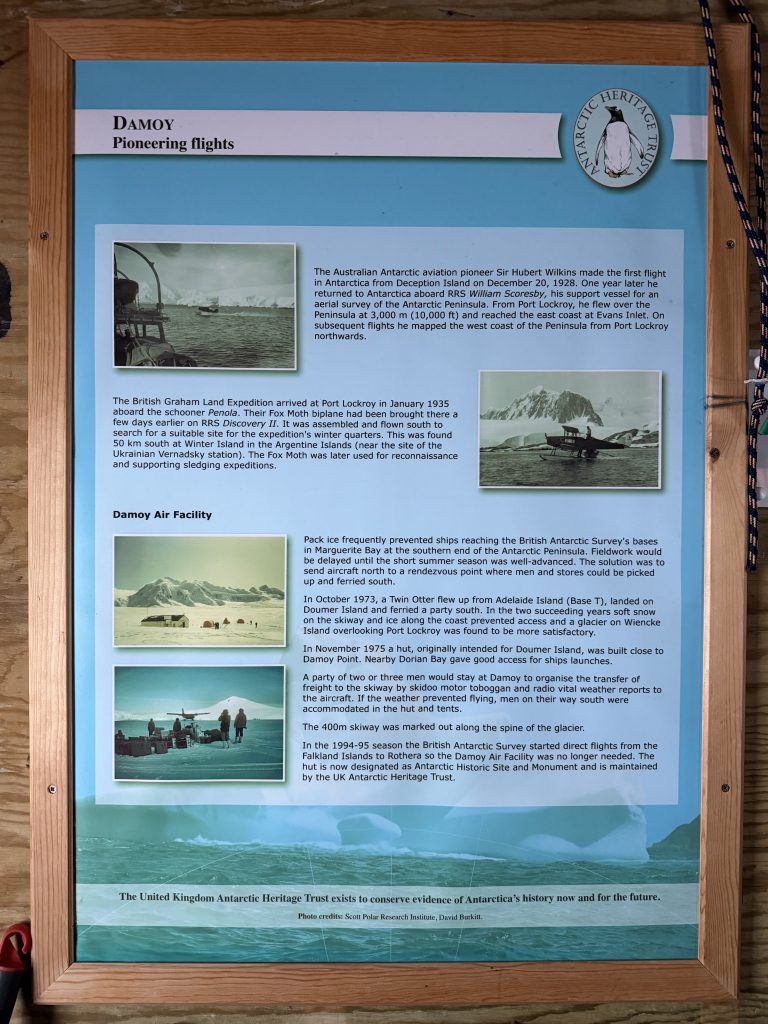

Once we had camp set up, the expedition team took us in small groups to tour the Damoy Hut. Once used as a “waiting room” for scientists who were trapped by sea ice heading to the Rothera Research Station, which coincidentally serves as the Capital for the British Antarctic Territory, the hut now serves as a museum to provide visitors an opportunity to step back in time and see what life may have been like before ships with satellite internet and saunas roamed these waters. Having left behind many books, canned food items, and other provisions, you truly get a taste of the desolate nature that Antarctica is famous for. One of the informative signs in the hut, pictured above, tells the stories of how this area was at one point used as a runway, sorry, skiway, to help supply these areas. So, more than just the amazing opportunity it was camping with the boys in bivy bags on Antarctic ice for the night, we did so on a backcountry airstrip. To commemorate this achievement, I sent Stefani a few inReach messages to let her know that we’re all tucked in for the night, the boys are warm, and we’ll see them shortly in the morning to come.

After an early wake-up, we returned back to the ship to set sail for our first continental landing in Orne Harbor. Peering above us, the errant penguin highways (pathways that have been “carved” into the snow and ice from their repeated trips to and from the water for food) scattered across the human highway, our designated trail to take us atop the mountainous shoreline. The expedition leaders reminded us that today’s landing would be our first (and only) landing on the continent of Antarctica, so the purists who didn’t count Petermann Island as a continental landing could rejoice once reaching the top of the five hundred foot incline, and stand together, and mark the occasion. The breathtaking views and surrounding landscapes once again proved difficult to photograph, or, at least, in a manner to convey the innate beauty that surrounded us. Only errant penguin chatter and the occasional glacial calving echoed through the horseshoe harbor and reminded us of the vast amounts of activity that many times appeared invisible to our eyes.

A few more hours of sailing, and we found ourselves arriving at Danco Island. Once again, we would be given the opportunity to grab some trekking poles (which, with the varying levels of snow and ice along the trail, were found quite useful) and assemble ourselves on our human highways to the top. As is customary, the penguins have the right-of-way, and occasionally, would break up the hiking party with their decision to join what appeared to be a good time. Much more exposed rock than before, Danco Island’s western slope was a mix of melting snow and loose rocks that I thought would have been a challenge for Oakli, but with much grace and poise she reached the summit herself. A few more penguin colonies were observed a little further away than usual, as the southerly winds meant that your nose knew the penguins were close quicker than your eyes. Some brave adventurers in our group decided to polar plunge themselves again off the beach of the island, none of the Evanses were so brave, or so bold, as your return to the ship (and warm, dry clothes, shower, sauna, hot tub, whatever your relief was going to be) was based on boarding a zodiac back to the ship.

Before sailing too far away from Danco Island, our opportunity to go kayaking as a family came. Since there’s an odd number of us, and through this trip have made friends with one solo adventurer, we adopted her into our group and bravely she kayaked with Luke as we maneuvered our mini-vessels around the various floating ice and penguins scattered across these waters. Spending some time together on the frozen water, level with the penguins that would leap in and out of the ocean, was quite the experience. Modest attempts to get video of penguins swimming underwater, much like I was able to catch of the boobies diving in the Galapagos, were futile. Similarly, trying to get the camera underneath an iceberg of modest size gave less than stellar results.

One last day in Antarctica, and the similarities between this and our Galapagos trip caught my eye. More than just the wildlife, the beautiful topography, and the thrill of the expedition, our last day in the Galapagos we found ourselves anchored inside the caldera of a volcano that formed Genovesa Island. On this day, we similarly sailed through a narrow passageway in the caldera to make our way further inside the natural harbor to spend some time in Telefon Bay. While the top of Genovesa Island was quite flat and home to millions of birds, the topography of Deception Island was quite more extreme. Hills and mountains made from various eruptions over the years (one of which was as recent as in the 1970s) make quite the backdrop for such a historic place. Deception Island was once home to a large whaling operation, and today, now houses a few scientific research stations, some relics of its former past as a slaughterhouse for the underwater giants that feed her, and even an old hangar that once supported the British Antarctic Survey’s aerial missions.

What most of the kids missed, having started off a few minutes ahead of us as we hiked atop Cross Hill, is the true challenge the climb was for our little Oakli. Throughout the entire trip we learned that 32ºF isn’t that cold, especially when the sun is shining, and that a well-built weatherproof outer layer can keep the warmth inside quite well. And as the days went on, we’d find ourselves warmer than necessary, deciding to shed some layers the next time we were headed through the Expedition Launch. However, as we traversed through Neptune’s Bellows into Deception Island’s interior, the winds, snow, rain, and cold air reminded us that if there was a day to bundle up, this would be it. Through the windows at our lunch table, we could see the faint yellow dots of our expedition leaders paving the way around what appeared to be the top of a volcano that would be our last time to set foot on our seventh continent. Alas, bundled beyond belief, binoculars and a Nalgene strapped to my belt, we took to the zodiacs, sailed through Stancomb Cove, and began what was the most arduous hike yet. The wind blew stronger than any day we had experienced, and even some of the expedition guides were worried that they might be strong enough to knock Oakli down. But a few adjustments to her gloves, buffs, hoodies, and outer layers (and two piggy-back rides), she climbed the over 650 feet to the top of Cross Hill saying “I’m so brave, I’m so strong, I’m so tough.” Two and a half miles later, one last zodiac ride, one last boot scrub, one last doffing of the multitudes of layers, we celebrated our achievements this week with a few hundred other brave adventurers, being serenaded by the Rolling Waves, the band made up of the crew (like our Cabin Steward Billy), dancing until the sun reached its lowest position against the horizon and we retired for the night back in our cabins.

The culmination of our world travels reminds me of the motto of Ushuaia, our launching off port from South America. “Ushuaia, fin del mundo, principio de todo,” translated, “end of the world, beginning of everything,” truly resonates in my soul. Surely, there’s a few more countries to visit. Indeed, there is some rumored “eighth continent” that we must visit as well. But the beauty of travel is not necessarily all about what you see. For me, lately, it’s been a lot more about how one feels. That awe-inspiring moment staring outward to the horizon, waiting for that first glimpse of Antarctic soil, the tears that slowly fell from my eyes remind me of the inherent beauty in all things. Whether we choose to see it or not is up to us. Our prejudices, our opinions, our experiences cloud our eyes, potentially keeping opportunities like this from being experienced. And more than just the sights and the sounds of these adventures, the thoughtful memories and tender moments we treasure in our souls will hopefully empower these adventures and expeditions into the future, because, sure, we may be at the end of the world, but we truly are at the beginning of everything.