the following words were written as part of a presentation I gave on Backcountry ADM as part of my involvement with the Backcountry Safety Coalition

Before I begin my dissertation, I want to share with you one of my favorite quotes from the great Wolfgang Langewiesche. “We pay attention to the wrong things; we miss the things that matter because we aren’t looking for them, because we do not know what they mean.” I love this quote because in the over 100 years of flying airplanes, we’ve somehow continued to repeat the faults of the past. We continue to take perfectly good airplanes and turn them into mere fragments of what they once were. Pristine paint jobs are marred with marks of these battles we face, sometimes with the environment, mostly with ourselves.

“We understand that for a treasure to be fully enjoyed it must be experienced and not merely read about in historical books,” reads a small sign on the windsock at Mexican Mountain. Backcountry aviation gives us the unparalleled access to some of the most amazing experiences across our great country. Within the range profile of most of our airplanes, we can transport ourselves deep into the wilderness, further than other machines could. Whether we’re seeking reprieve from the instant-notifications of today’s modern world, or yearning for the opportunity to reconnect with nature, the backcountry welcomes us all who respect the challenges that come forth, and handle said challenges responsibly.

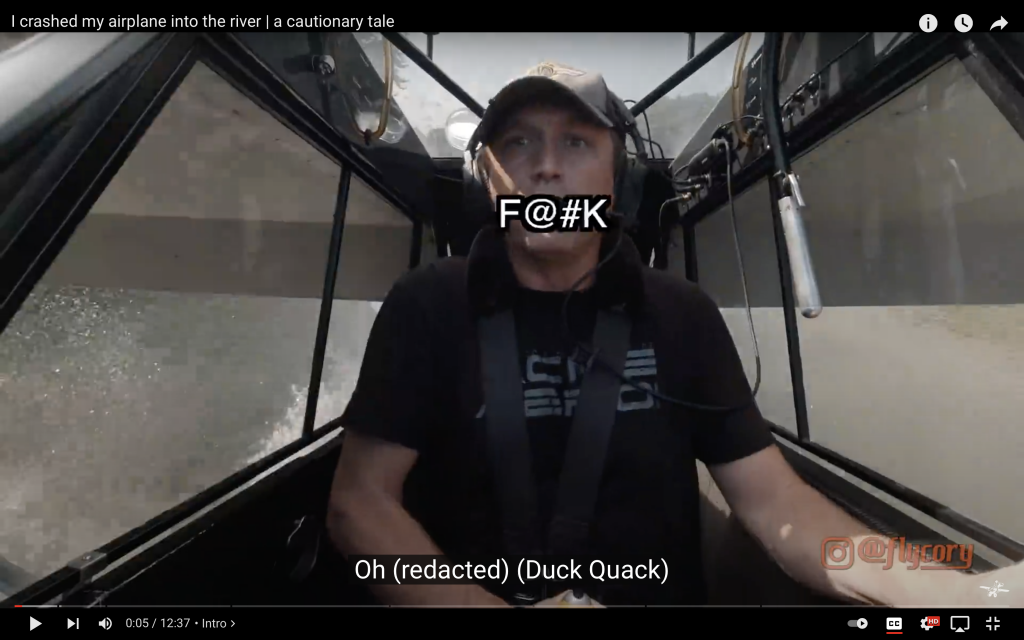

We’re all intimately familiar with the phrase “Hindsight is 20/20.” The concept that after a decision is made and the outcome presents itself, we can easily deduct the reasoning behind that decision far better than could have been done before. And for outsiders of these decisions, the process is even easier. But within aviation, hindsight is more than 20/20. Hindsight is now in 4K, 360 degree footage with multiple angles and even close captioned for the hearing impaired.

“A little more rushed than normal” explained one pilot, as he shared the tale of his accident to a captive audience. “A momentary lapse” in judgement put him into a position he thought that he “knew what the plane was going to do.” While discussing the loss of control accident at Oshkosh, the pilot shared that “it doesn’t matter how many hours you have…you’re vulnerable,” especially when you find yourself “pushing the limits too far.”

Succumbing to the self-proclaimed pitfalls of “not using [his] normal procedures,” another pilot admitted that “I totally screwed up.” The distractions of the mission to “get the shot for this YouTube thing” tied in with a homemade auxiliary fuel tank, eventually took over leaving the pilot with “no excuses” for what happened next.

“Probably one of the worst days of my life,” shared another pilot after coming to rest alongside the runway. Noting the “big black storm” approaching the airport with a “real gusty crosswind,” the airplane saved the pilot and his passengers from injury. “The plane did not fail me. I failed the plane and the passengers. Obviously, I am going to learn from it, and I hope others will as well.”

All three of these pilots highlight the powers of hindsight. In each of these accidents, the pilots were quite clear on exactly what happened. They, without resistance, admit to themselves and to their fans that they messed up. While I haven’t interviewed each of the pilots, I’m certain that while these videos serve as some of their highest engaged content online, their intention was not to thrust themselves into harms way for a few more views.

So if hindsight is 20/20, what is foresight? If we all could be fortune tellers, life would be a little different. But one does not need to be entangled in the dark arts to help influence them in the many decisions we make as backcountry aviators.

How we go about gaining foresight? First we have to learn to listen. Langewiesche speaks volumes about how pilots must learn to read what their airplanes are telling them…without the use of their eyes. Accident investigations across all modes of transportation paint murals of the perils of distractions, whether they be internal or external. And if our community is quick to install the latest doodads in the name of performance, what are we doing within ourselves, our machines, and our environments, to maximize our capabilities?

If we take these concepts and apply them to you, your airplane, and your environment, we can better equip ourselves with the information that will help us make better decisions.

Starting with you, recognizing the physiological and psychological affects that can impact our ability to manage the varying workloads in backcountry flying need to be accounted for. The IMSAFE checklist does a great job of having us take a few moments to assess those areas, and this process, or others similar to it, should be one of the first things we do in our preflight planning. While we’re bound by the legal requirements regarding currency, the onus is on us to set the standard higher with regards to competency. Beyond the hours and landings, a review of our previous flights and the performance we saw in ourselves on those flights will help us come to a conclusion regarding whether we are ready for the challenges that lie ahead. On top of all this is the ability to recognize threats within ourselves, whether they manifest as the pressure to perform, confirmation bias, the priming that subliminally pushes us to complete a flight that’s been in the planning stages for weeks. Identifying these threats and determining whether they can me mitigated or not are skills that have been proven to enhance the safety of flight operations, and currently serve as the cornerstone of CRM training throughout commercial aviation.

When we talk about our airplanes, we tend to speak highly of our abilities to operate them. The constant quest to master control of our aircraft should be something we strive for on each and every flight. Setting a standard for how we fly our airplanes, holding ourselves to that standard, and increasing those standards helps us truly master our airplane. And while we’re working on that mastery, there’s a distinct difference between practice and perfect practice, and setting aside flights with the sole intention of completing this practice, perhaps with the support of a mentor, a competent CFI, or at the least, a second set of eyes, should be part of our on- and off-season flying regimen. While we talk about increasing the performance capabilities of our airplanes, we must consider the concept of risk homeostatis, where the installation of STCs and other modifications push pilots to arbitrarily increase their acceptable risk levels, many times without exercising these enhancements and learning what their new limitations may be.

In these challenging environments which we find ourselves, it’s imperative that we have an intimate knowledge of these airstrips before we leave home base. Old timers tell tales of their phones ringing off the hook with out-of town pilots coming to town looking to learn more than a sectional could provide. These days, hundreds of thousands of hours of YouTube videos compete with this tribal knowledge for attention. However you get it, knowing what to expect increases your ability to operate safely in the backcountry. And while you may have something like our gold-standard ForeFlight content pack to let you know what to expect at an airstrip like Hidden Splendor, learning the skills necessary to assess airstrip conditions, such as that of the surface, surrounding terrain, and weather, can and will keep you from learning valuables lessons the hard way. In the end, weighing the risk versus the reward of flying in the backcountry, into our desired airstrip, is a discussion that should have been completed prior to engine start, and is then validated prior to landing.

Revisiting how we enhance our decision making skills in the backcountry, I have learned that learning to listen to ourselves, our airplanes, and our environments are skills my mentors have impressed upon me, and which I share with those I mentor. Removing distractions, from ourselves, our airplanes, and our environments, we can steer our intended course in a safe, fun, and efficient manner, provided we can mitigate those challenges we identify. Through all this, maximizing our performance, our airplane’s performance, and our environments, we can find ourselves in places where our superior judgement can help us avoid stressful situations which might call for the use of our superior skills.

While this presentation certainly isn’t sufficient to empower us all with the abilities to make better, sound decisions while flying in the backcountry, a community of like-minded individuals is. A community that donates their time and their talents to not only the backcountry itself, but to the future stewards of it as well. One that holds its members and themselves accountable, embraces safe, ethical flying practices, and does so in a manner consistent with the respect and responsibility this kind of flying requires. These communities empower their members with the shared experiences dispensed over the campfires at some of our favorite airstrips across the west, and build upon the foundations that have made these campfires and airstrips possible.

Communities and mentors aside, the only thing stopping us from making a bad decision is ourselves. When we don’t pay attention to ourselves, our airplanes, or our environments, is it any wonder we continue to fall prey to pilot error?

I’m reminded of one of my adventures where on go-home day the weather was less than ideal. Those who succumbed to their schedules were left fighting against Mother Nature, with one airplane reporting the worst turbulence they’ve had to endure the whole four hour flight home, and two others having to change plans altogether when one ended up ground looping at a fuel stop. Those of us who waited two days for better conditions were rewarded with beautiful vistas and smooth rides the whole way home. Mother Nature was speaking loudly the whole time, but only some took the time to listen.

A lesson on listening to our airplanes, I’m reminded of a time I helped my best friend complete a pre-purchase agreement on a modified experimental Super Cub. A clean paint job, a recently redone interior, and logbooks that matched made this opportunity seem sound. What didn’t, however, was sitting in the pilots seat and exercising the controls through their full range of motion, where the real story of the airplane’s previous damage history and hastily-reassembled bits and pieces from hangar scraps made a recently completed conditional inspection worthless, in addition to a wretched grinding noise.

And finally, when it comes to us. We have to listen to ourselves more than anything else. For months I had made preparations for attending one of our fly-ins, and while the weather models appeared to tell a story of favorable conditions, those models changed for the worse as departure day approached. Arriving at my hangar, something didn’t sit well with me. Initially, I was upset that I forgot my window washing solution, but figured I could do without the cleanest airplane at the fly-in for a change. But then I found myself dismissing points of contention in the final stages of the preflight process. The winds on the surface, aloft, and the ever-changing models fought against me wanting nothing more than to load up and take-off. But that bottle of window wash I left at home helped me realize my body is trying to tell me something, and a pleasant drive with a great friend to the fly-in confirmed that while the weather may have been questionable, the risk of getting stuck on the way home and succumbing to the deteriorating weather wasn’t worth it.

In conclusion, ADM in the backcountry is a lesson that spans multiple lifetimes. Pilots well-revered for their safe, responsible practices are more than willing to share their experiences with the younger up-and-coming backcountry aviators out there…all they need to do is ask. And all we need to do is to listen. To them. To ourselves. To our airplanes. And to our environments. If we can seek those opportunities, those conversations, perhaps we won’t miss those things that Langewiesche laments about, and we’ll learn how to make foresight, not hindsight, better than 20/20.